India Bans Transshipment Facility for Bangladesh after Chinese Puppet Yunus’s illogical remarks

Northeast India was, is, and will always be an integral part of Bharat. In a move that has sent ripples through South Asian geopolitics, India has abruptly ended a key transshipment facility that allowed Bangladesh to route its export cargo through Indian territory to third countries. The decision, effective immediately as of April 8, comes days after Muhammad Yunus, the chief adviser of Bangladesh’s interim government, made controversial remarks during a visit to China, suggesting that Bangladesh could serve as a maritime gateway for India’s “landlocked” Northeast, potentially extending Chinese economic influence into this strategically sensitive region.

The termination of this facility, which had facilitated Bangladesh’s trade with Bhutan, Nepal, and Myanmar since 2020, marks a significant escalation in the already strained relations between New Delhi and Dhaka, raising questions about regional stability and Bharat’s response to an emboldened Chinese presence in its backyard.

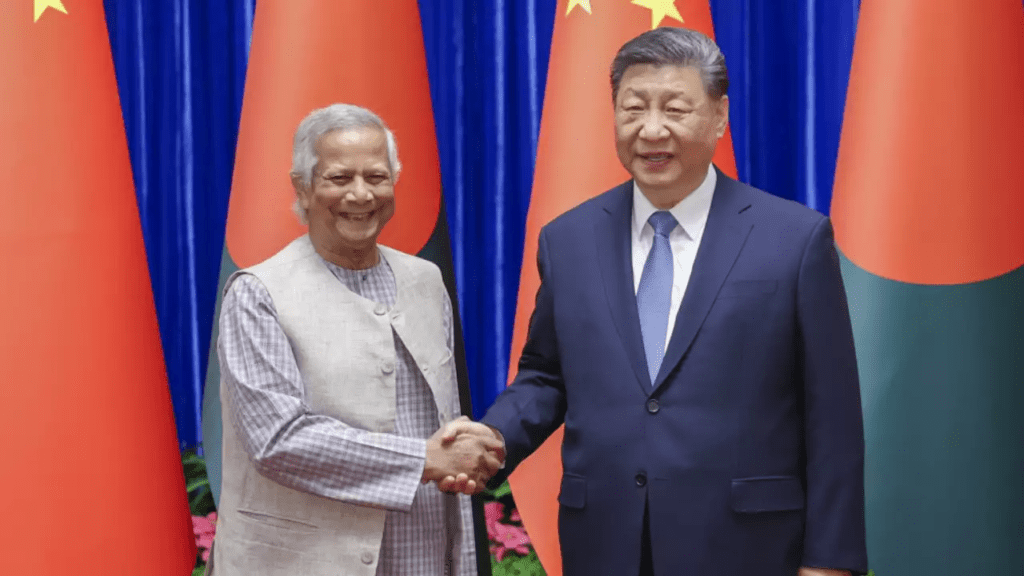

The Backdrop: Yunus’s China Visit and the Northeast Remark

The spark for this diplomatic flare-up ignited during Yunus’ four-day visit to China from March 26-29, where he met with President Xi Jinping and signed nine agreements aimed at deepening Sino-Bangladeshi ties. Speaking at a high-level roundtable in Beijing, Yunus described India’s northeastern states—often referred to as the “Seven Sisters”—as a “landlocked region” with “no way to reach out to the ocean.”

He positioned Bangladesh as the “only guardian of the ocean” for this area, suggesting it could become “an extension of the Chinese economy” by producing goods, marketing them, and connecting them to global trade routes via Bangladesh’s ports. “This opens up a huge possibility,” Yunus said, framing Dhaka as a critical conduit for Beijing’s economic ambitions in South Asia.

The remarks, widely circulated via videos shared by Bangladesh’s interim government on social media, triggered immediate backlash in India. Assam Chief Minister Himanta Biswa Sarma labeled them “offensive” and “strongly condemnable,” arguing that they underscored the vulnerability of India’s Siliguri Corridor, colloquially known as the “Chicken’s Neck”—a narrow 22-kilometer strip of land connecting the Northeast to the rest of the country. Sarma called for alternative infrastructure to bolster connectivity, while other Indian leaders, including Congress’s Pawan Khera, accused Yunus of inviting China to “encircle India,” pointing to Beijing’s existing claims on Arunachal Pradesh and its infrastructure buildup along the Line of Actual Control.

India’s Response: A Strategic Retaliation

India’s decision to rescind the transshipment facility, formalized through a circular from the Central Board of Indirect Taxes and Customs (CBIC) on April 8, appears to be a calculated retaliation. The facility, introduced in June 2020, allowed Bangladeshi export cargo to move through Indian Land Customs Stations (LCSs) to ports and airports, streamlining trade with Bhutan, Nepal, and Myanmar. Its termination, though framed by the Ministry of External Affairs as a logistical necessity due to “congestion at our airports and ports,” is widely interpreted as a signal to Dhaka—and Beijing—that New Delhi will not tolerate moves that threaten its strategic interests.

The Ministry clarified that the withdrawal does not affect Bangladesh’s exports to Nepal or Bhutan transiting through India, but trade experts warn that the broader impact could be significant. “This streamlined route cut transit time and costs,” said Ajay Srivastava, founder of the Global Trade Research Initiative. “Now, Bangladeshi exporters may face delays, higher expenses, and uncertainty.” Sectors like apparel, footwear, and gems—where Bangladesh competes fiercely with Bharat—could feel the pinch, potentially benefiting Indian exporters who have long complained about capacity constraints caused by Bangladeshi cargo.

The Geopolitical Chessboard: China’s Growing Shadow

At the heart of this spat lies the specter of China’s expanding influence in South Asia. Yunus’ pitch to Beijing wasn’t just rhetoric—it came with concrete proposals. During his visit, China pledged $400 million for Mongla Port, $350 million for the Chinese Economic and Industrial Zone in Chattogram, and $150 million in technical assistance. Reports also suggest Bangladesh has invited Chinese investment to upgrade an airbase in Lalmonirhat, near the Siliguri Corridor—a move that has heightened India’s security concerns. With Beijing already asserting claims over Arunachal Pradesh and building dams on the Brahmaputra River, the prospect of Chinese economic and military footholds in Bangladesh is a red line for New Delhi.

India’s Northeast, comprising eight states, is a geopolitical flashpoint. Connected to the mainland only through the Chicken’s Neck, it shares borders with Bangladesh, China, Myanmar, Bhutan, and Nepal. Any disruption here—whether logistical, economic, or military—could destabilize India’s eastern flank. Yunus’s remarks, intentional or not, tapped into this vulnerability, amplifying fears of encirclement at a time when India-Bangladesh relations are already fragile following the ouster of Sheikh Hasina’s government in August 2024.

Domestic and Regional Reactions

In India, the decision has drawn mixed responses. While some hail it as a decisive stand against Bangladesh’s pivot to China, others question its long-term wisdom. Trade analysts note that the move could strain India’s commitments under the World Trade Organization’s Trade Facilitation Agreement, which mandates efficient transit for landlocked countries—a category that includes Nepal and Bhutan, both reliant on Indian routes. “This could invite diplomatic pushback,” warned one expert, speaking anonymously.

In Bangladesh, the reaction has been muted, with Yunus’ interim government yet to comment officially. However, the economic stakes are high. With the country grappling with financial woes post-Hasina, Chinese investment is a lifeline Yunus cannot afford to lose. Yet, by antagonizing India—a neighbor that has historically offered zero-tariff access to Bangladeshi goods—Dhaka risks overplaying its hand.

A Fragile Balance: What Lies Ahead?

The termination of the transshipment facility is more than a trade dispute—it’s a chapter in the broader saga of South Asian power dynamics. For India, it’s a reminder of the challenges posed by a resurgent China and an unpredictable Bangladesh. For Yunus, it’s a test of his interim government’s ability to navigate a delicate balancing act between economic survival and regional diplomacy.

Critics argue that India’s response, while assertive, may push Bangladesh further into China’s orbit, undoing decades of goodwill built under Hasina’s tenure. Others see it as a necessary flex of muscle, signaling that New Delhi will not cede its strategic backyard without a fight. Meanwhile, the Northeast remains a tinderbox—its isolation both a liability and a rallying point for India’s security establishment.

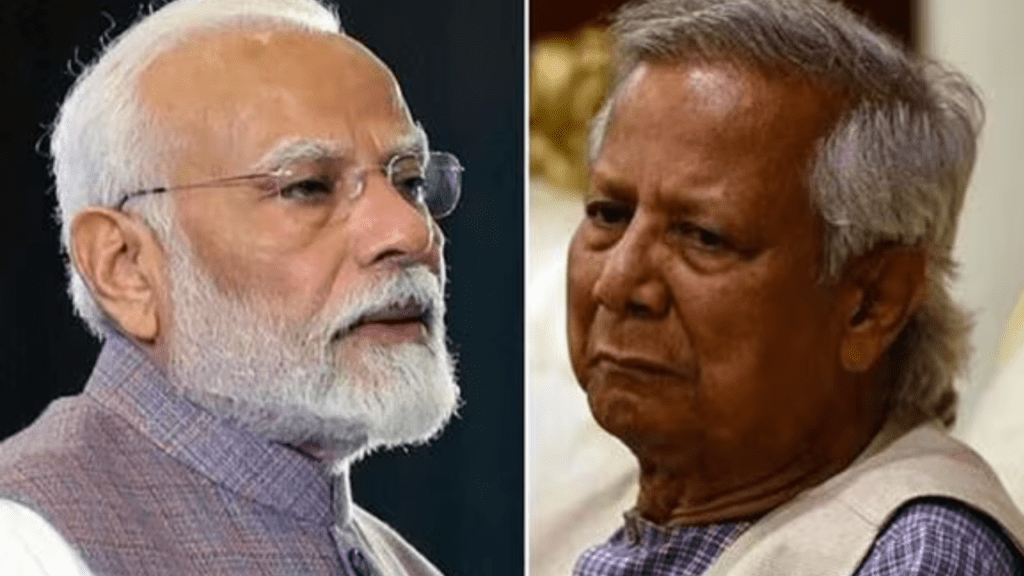

As the dust settles, all eyes are on the upcoming BIMSTEC summit in Thailand, where Yunus has requested a meeting with Prime Minister Narendra Modi. India has yet to confirm, leaving the prospect of dialogue uncertain. For now, the transshipment rollback stands as a bold marker of intent—one that could reshape alliances and rivalries in a region already teetering on the edge of transformation.